Surveys are sometimes considered a more informal and easier-to-use research instrument in Psychology. But designing good surveys that can capture meaningful effects in an unbiased and interpretable way is a complex skill. In this article, we’ll cover some of the most common errors that researchers make when designing surveys. Some of these errors tend to occur because they reflect an unconscious desire of the researcher to push the results in a certain direction. It is therefore very important to audit your own survey for the following problems before you start collecting data.

One common mistake in survey design is asking leading or biased questions. Leading questions are those that suggest a particular answer or steer the respondent toward a specific response. This can invalidate the data collected, as the respondent is not freely choosing their answer but rather is influenced by the wording of the question. We might for example want to find out how our users find our latest feature launch on Testable and ask:

“How much did you enjoy our improvements to results exporting?”.

This wording already implies that the user did in fact enjoy the feature (or at least ought to). It can influence ratings even if “I did not enjoy it” is among the answer options.

If you want to collect more informative results, you should therefore aim to frame any question as neutrally as possible.

Example:

“How would you rate our improvements to results exporting?”

Biased questions

Similarly, loaded questions also will skew results by assuming a part of the answer. In our example survey we might ask our users:

“How often do you export results data with over 50 results?”

In this question, we are already assuming that our users all export results. Even if we included an option “I never export results data with over 50 results” we would not know if that is because they never pass the 50 result threshold, or perhaps because they never collect data at all. It is better therefore to construct “funnels” using neutrally framed questions. For example:

“Do you collect any experimental data using Testable”

If yes →

“Do you ever export data files with more than 50 results at once?”

If yes →

“How often do you export data files with more than 50 results?”

Don’t worry about adding extra questions to your survey if it helps reduce complexity. It can actually feel easier for participants to reply to multiple simple and logically building-up questions than to decode a single, more complicated question.

In an ideal world, two people who think or feel the exact same thing would also give the exact same response to your questions in the survey. Of course, it is unavoidable that your participants will interpret your questions slightly differently, and that you will have to account for the resulting variability. But in the design stage, it is your job to allow for as few misunderstandings as possible, so that responses between participants are comparable.

Example:

“Have you felt anxious in the past week”?

In informal conversation, the above question might seem clear enough. But you’ll notice that there are at least two terms in this question that are ambiguous and might lead to distorted responses. The term “anxious” can mean different things to different people. Are you looking to capture symptoms of anxiety disorder or do you also care about fleeting sensations of stress and possibly even “good” anxiety, like the nervousness before a promising job interview? Further, “past week” is also ambiguous. If today is Tuesday, would you mean the past 7 days, the past week up to last Sunday, or the time since yesterday, the beginning of a new work week? Here is clearer framing of the same question:

“In the past 7 days, have you experienced severe feelings of anxiety that prevented you from pursuing day-to-day activities such as going to work, meeting friends, or running errands”?

It more clearly defines the time frame of interest and explains what we mean by “anxiety” using examples of specific behaviors.

Better yet, instead of framing this question as a yes or no question, you instead allow your participants to select the types of experiences and symptoms they have encountered in the past 7 days. This will add some analysis overhead, but will also reveal a more accurate and granular picture of your participants’ behavior:

“Please indicate which of the following experiences you have encountered in the past 7 days:”

To ensure that questions are clear and straightforward, it is helpful to pilot test the survey with a small group of people to ensure that the questions are being understood as intended.

Assume we are conducting a short service to measure the satisfaction with our participant pool Testable Minds. One of the questions could be:

“How satisfied are you with the overall quality and cost of Testable Minds?”, followed by a 5-point scale ranging from “Very unsatisfied” to “Very satisfied.

Can you see the problem? We would not know if the scores we received back reflect the quality, the cost, or some weighted average between the two. The interpretation may also vary between participants based on their personal priorities.

So instead you might ask two separate questions, to understand perceptions of cost and quality separately.

1. “How satisfied are you with the overall quality of data you receive from Testable Minds?”

2. “How satisfied are you with the costs of recruiting participants on Testable Minds?”

To achieve results that are easy to interpret, make sure that with each question you ask one thing, and one thing only. And as mentioned above, don’t be afraid to add more questions if it helps create a more straightforward experience for participants.

There are loads of different ways that you can capture responses in surveys. It is therefore important to consider the impact of your design on the data you’ll receive. Like with many effects in behavior science, small changes can have a meaningful impact. It is therefore important to consider even small details.

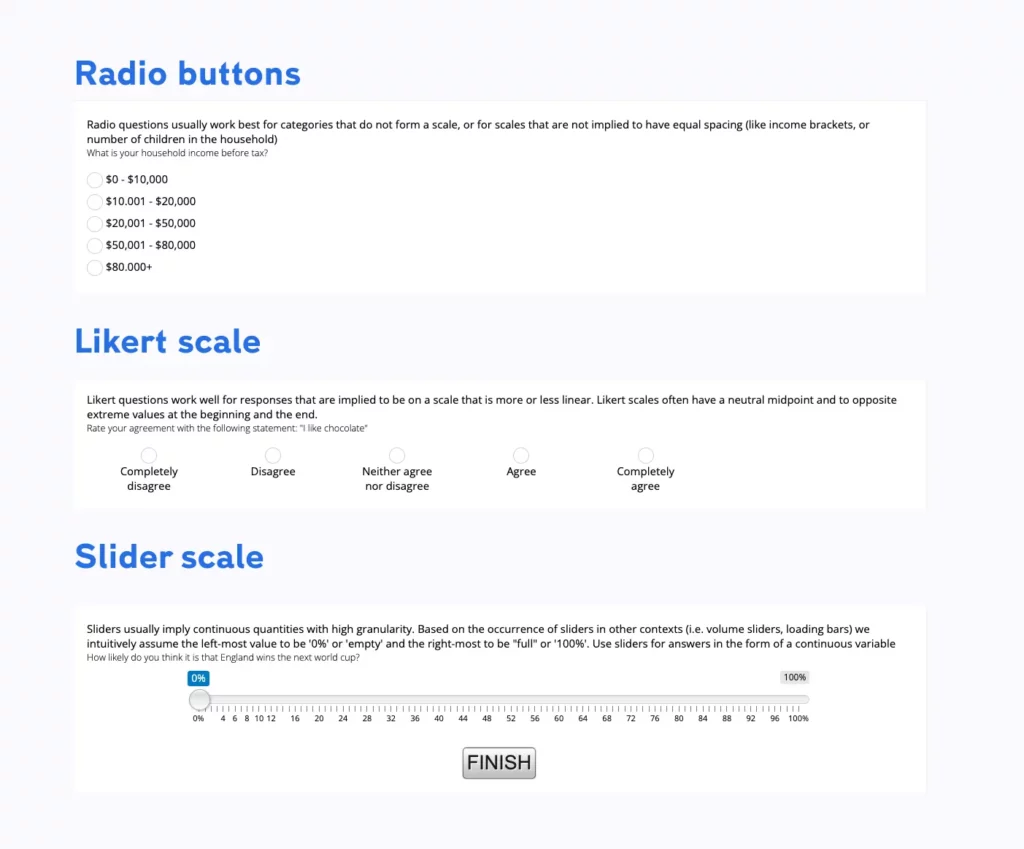

Sliders vs. Radio buttons vs. Likert scales

Take for example the difference between radio buttons, Likert scales, and slider selections. They all allow participants to pick exactly one response from a defined set of response options. Any multiple-choice question with only one answer could be measured with any of these methods interchangeably. Yet, each scale will evoke slightly different meanings in the participants’ minds.

Sliders usually imply a continuous measurement scale where fine gradings are possible and plausible. A slider set to the leftmost value usually implies “empty”, “none”, or “0%” and the rightmost “full”, “100%”, or “completely” (think of volume sliders or progress bars). It might therefore be confusing to use sliders where the left-most and right-most values are on opposite sides of an extreme. For example, an agreement scale that ranges from “totally disagree” → “totally agree”, with a neutral mid-point (“neither, nor”) does not map well on the intuitive interpretation of a slider.

A better alternative here would be the use of a Likert scale, ideally with each of the values labeled appropriately. Likert scales more clearly convey that the available options are meant to represent ranks on a scale. It is also more consistent with the idea of a bipolar scale (two extremes) with a neutral center point. This means that participants will be more likely to use the full range of the scale intuitively, giving you a more accurate range in your response data. Your specific question and the kind of answer you are expecting will determine the best response type.

This brings us to another consideration:

When using a scale, how many response options should you give?

Choosing the granularity of your scale (5 points, 7 points, 11 points, 100 points…) is an important consideration as it will significantly determine the texture of the data that you’ll receive. The more options your offer, the greater the range of responses will be that you will receive. This can be a good thing if there are meaningful and understandable differences between options. Granular scales can reveal smaller, but significant effects that would have been hidden if participants were forced to choose between coarser options. On the other hand, more response options also introduce more noise. If you consider grouping multiple responses for analysis anyway, it might be a good idea to offer fewer options in the first place. It is better to leave it to your participants to make a choice between categories (i.e. agree, vs, strongly agree) than to impose it on them in analysis.

As a rule of thumb, fewer options that are meaningfully labeled will work better, unless you have strong reason to believe that participants will make a meaningful distinction between finer grades. Or in other words: Don’t increase the granularity of a response scale beyond necessity.

Finally, make sure that you’ll audit your survey for broken scales. If your options don’t exhaust all logical options or the available options are not mutually exclusive, you have a broken scale. It’s easy to miss broken scales and they will give you headaches during analysis.

Here are some classic examples of broken scales:

How many children do you have?

At first glance, the options seem reasonable. But you’ll notice that people with exactly two children can pick option 1 or 2 and those with three children options 2 and 3. Make sure that for any plausible answer, there is exactly one answer option on your scale. Here is how the scale would make logical sense:

How many children do you have?

This mistake can also happen in the other direction if you are missing an option:

What is your yearly income before tax?

Although we’ve added an option for people who don’t earn any money, someone who does earn, albeit less than $20k/year, would not have any option to pick.

Generally, it is a good idea to pilot your survey with a few real participants before you launch the real fieldwork. In this pilot study, you should add an extra question at the end, or in-between sections, that prompts participants to give feedback. Something like “Do you have any comments or feedback about the survey? Were there any questions that you had difficulties with or that did not make sense to you?” followed by an open response text box will work.

You can easily build survey experiments in Testable. You can get started by using our Universal Template and choosing “I want to build survey questions” or by picking one of our ready-made questionnaires. A detailed guide on how to work with surveys and forms is available here. If you ever get stuck or have any questions about how to implement your surveys in Testable or about survey best practices then why not get in touch? We’re looking forward to hearing from you 😊.